Bay Water Temperatures Increased 1.6°C (3°F)

in Three Decades

Inshore Waters May Be More Vulnerable to Water Quality Problems

WHY IT MATTERS

Water quality refers to physical, chemical, and biological properties of the waters in an aquatic ecosystem. This chapter focuses on six measures of water quality in the Bay: temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, water clarity, pH, and chlorophyll. These measures provide insight into how the biology of the Bay interacts with physical mixing processes to produce clean waters that support healthy fisheries and coastal ecosystems. The chapters on Nutrients, Shellfish and Swimming Beaches, and Coastal Acidification present closely related information on the Bay’s water quality.

Friends of Casco Bay (FOCB) staff and volunteers have monitored water quality at dozens of sites since the early 1990s, making it possible to develop an understanding of how the Bay is changing and how conditions vary among regions of the Bay. Recent adoption of new continuous monitoring technologies by FOCB, University of Maine, and Maine Department of Environmental Protection is further expanding our understanding of water quality.

STATUS & TRENDS

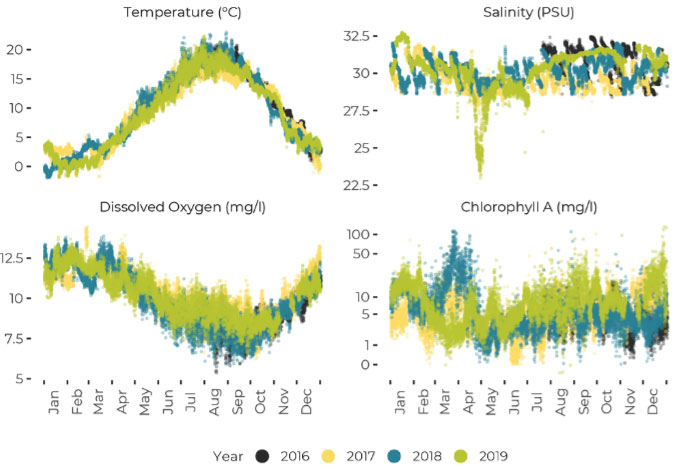

Continuous Monitoring Reveals Seasonal Changes

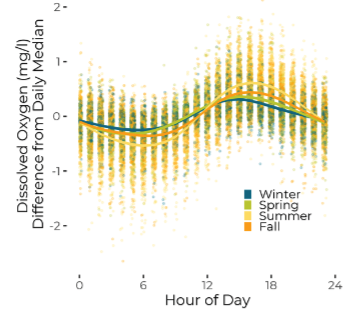

Dissolved Oxygen Daily Cycle

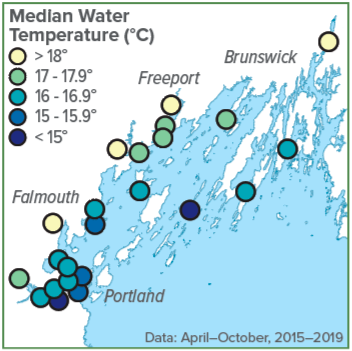

Temperature Hints at Vulnerability to Pollution

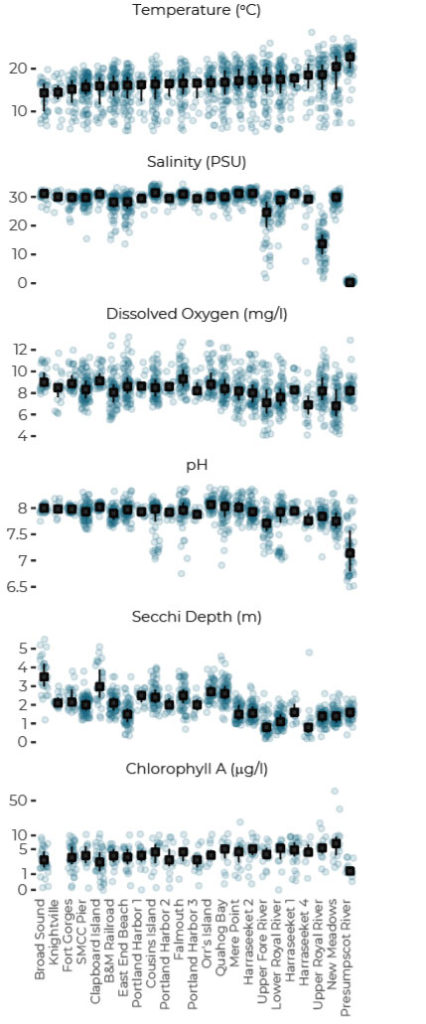

Water Quality by Location

Long-term Bay-wide Trends

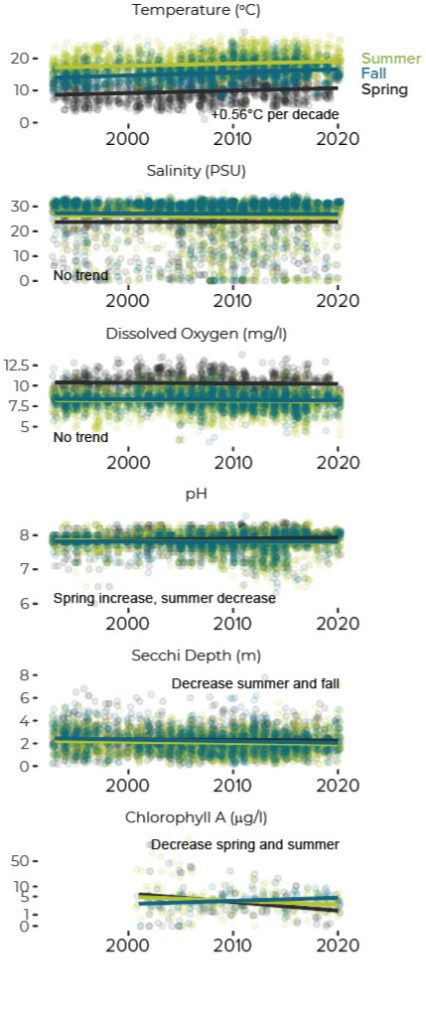

Measures of water quality

Temperature and Salinity: Water temperature and salinity reflect and influence patterns of water mixing. In Casco Bay, summer water temperatures provide a rough indication of the degree to which conditions are dominated by offshore waters. Salinity values show the effects of river and stream discharge, especially the Presumpscot and Kennebec rivers. Cooler or saltier water is denser than warmer or fresher water. Thus differences in temperature or salinity can reduce water mixing in estuaries, shaping spatial water quality patterns.

Dissolved Oxygen: Low dissolved oxygen conditions can stress marine organisms, but oxygen is also an indicator of biological activity. Oxygen levels reflect the balance between photosynthesis and respiration as mediated by physical processes like the mixing of surface and bottom waters. Diurnal fluctuations, for example, can reveal the interplay of respiration (which consumes oxygen throughout the day and night) and photosynthesis (which releases oxygen in daylight). Oxygen is more soluble in cold water, so low dissolved oxygen—a hazard for marine organisms—is most likely in early morning during summer months, when waters are warm.

pH: pH is a measure of the concentration of hydrogen ions in solution. Ocean waters tend to have pH near 8. Maine rivers generally have pH below 7. Site-to-site differences in pH reflect relative contributions of marine versus fresh water. Carbon dioxide from biological activity also affects pH in the Bay.

Secchi Depth: Secchi depth measures water clarity based on how deep an observer can see a dinner plate-sized disk – the greater the Secchi depth, the more transparent the water. Water clarity principally reflects the abundance of algae and suspended sediments in the Bay, but it is also influenced by colored dissolved materials. Poor or declining water clarity can be an indicator of water quality problems, especially if accompanied by other signs of excess phytoplankton abundance.

Chlorophyll a: Chlorophyll is the dominant photosynthetic pigment in phytoplankton. It is commonly used as a measure of the abundance of phytoplankton in coastal waters. Excess nutrients, especially nitrogen, may increase phytoplankton abundance or help trigger blooms.

successes & challenges

- Conditions in much of Casco Bay remain good, because Maine’s large tides bring in cooler, salty, offshore waters, thus helping to protect the Bay from water quality problems.

- Inshore waters have limited tidal mixing, shallow depths and naturally warmer water, making them more vulnerable to many water quality problems. They are also more directly influenced by runoff, discharges, and other human activity.

- Rising water temperatures are a reminder that climate change already affects conditions in the Bay. Warmer waters are expected to lead to changes in organisms found in the Bay, affecting fisheries, tourism and recreation.

- Water quality monitoring is transitioning towards more automated sensors, more continuous data, and fewer locations. This improves understanding of daily, tidal, and seasonal changes in water quality at those locations. Discrete monitoring at other locations remains essential for understanding conditions around the Bay.

View a PDF version of this page that can be downloaded and printed.

View references, further reading, and a summary of methods and data sources.

STATE OF CASCO BAY

Drivers & Stressors

What’s Affecting the Bay?

Human Connections

What’s Being Done?

If you would like to receive a printed State of Casco Bay report, send an email request to cbep@maine.edu.

This document has been funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency under Cooperative Agreements #CE00A00348-0 and #CE00A00662-0 with the University of Southern Maine.

Suggested citation: Casco Bay Estuary Partnership. State of Casco Bay, 6th Edition (2021).

Photo at top of page: Jerry Monkman, Ecophotography.com